Preservation + Conservation = 30%

Protected areas get the most attention, but conserved areas are important too.

The 188 signatory countries of the UN Global Biodiversity Framework have agreed to protect 30% of their land and ocean area by 2030. Last month’s blog examined how the EU is doing this.

Since then, BC has announced how it plans to protect 30%. On November 3, the governments of Canada and BC, together with several Indigenous organizations, signed the Tripartite Framework on Nature Conservation. Here’s a brief summary:

BC will protect or conserve 30% of its lands by 2030.

The BC and federal governments will each provide a significant amount of money for conservation initiatives.

The three levels of government that were signatory to the agreement (federal, provincial, and First Nations1 ) will work towards the protection of species at risk.

Although industry groups have been relatively quiet about the agreement, several environmental groups published press releases coinciding with the government announcement. For the most part, the groups celebrated the announcement. However, some suggested the new agreement does not go far enough.

Preservation ≠ Conservation

Among the concerns voiced was a Wilderness Committee observation that industrial activities could still be allowed in protected areas. Speaking to City News reporters, campaigner Charlotte Dawe criticized the Tripartite Agreement’s conservation standards as being “incredibly weak”, stating,

“…You cannot say an area is protected if you are still allowing mining, logging, oil and gas. If that were the case, we could say 100 per cent of B.C. is protected right?”

Ms. Dawe’s statement is in fact true: an area can’t be truly “protected” if industrial activity is permitted there. However, she misses a key distinction between preservation and conservation. While preservation seeks to protect nature by preventing its use by humans, conservation seeks to keep nature healthy through careful, sustainable use.

BC’s 30% will include both protected and conserved areas.

What Are “Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures”?

Referring to the 30% to be protected or conserved, the Tripartite Agreement states,

“This could include any combination of federal, provincial, municipal or Indigenous-led protected areas, and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) that meet national accounting standards and are reported in the Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database (CPCAD).”

Here is how the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) describes OECMs:

OECMs complement protected areas and are equally important for maintaining biodiversity, even though they may not be managed primarily for conservation. They should achieve the same level of in-situ or whole ecosystem biodiversity conservation as protected areas.

OECMs are not meant to be multiple-use production areas (e.g., production forests, plantations and fisheries areas) that are managed with some biodiversity considerations. While such areas are important, they should be counted toward additional sustainable use targets and not toward the 30% conservation target.

In other words, both protected areas and OECMs are important, and both must achieve biodiversity goals, but OECMs have more flexibility in how they can do that.

Why Allow (Limited) Resource Use in Conserved Areas?

As mentioned in the IUCN definition, conserved areas complement protected areas; for example, in Europe, the Natura 2000 areas provide connectivity between protected areas. Because much of Europe’s land base is privately owned and densely populated, it would be difficult to reach the 30% target without including private land in the mix. By designing conservation programs that are flexible enough to be achievable by private landowners, Natura 2000 has greatly increased the amount of European land under conservation.

In BC, only about 5% of the land is privately owned. However, much of the province is subject to unsettled Indigenous land claims. Because BC has committed to adopting the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the province will need to consult with First Nations prior to creating new protected and conserved areas.

The Tripartite Agreement recognizes this. Responding to a reporter’s question at the live press event, Nathan Cullen, BC’s Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship, explained OECMs thusly:

“We have evolved our thinking to incorporate the [fundamental] rights of Indigenous people. We know that adaptive management requires us to think of conservation in a new and important way given the changing environment in which we live… There will be modified activities, but [also] conservation efforts in terms of protecting the biodiversity that’s at risk…”

This does not mean that conservation areas will become industry hotbeds; rather, it recognizes that First Nations may wish to allow traditional activities (such as hunting) and economic development (such as tourism, road building, or mining exploration) on land within their traditional territories. Historically, most parks and protected areas omitted such activities.

An Example Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA)

OECMs are relatively new in Canada. According to the Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database, the majority of the country’s registered OECM land is in the BC and the Northwest Territories (NWT).

Conservation areas range in size and focus. Some, such as BC’s Wildlife Habitat Areas and Old Growth Management Areas, can be relatively small, and are designed to manage for specific wildlife species or values. Others, such as the NWT’s new Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs), cover vast territories and manage for a variety of different objectives. First Nations in BC are also negotiating IPCAs and more have been proposed. For example, the Ktunaxa Nation is developing the Central Purcell Mountains IPCA.

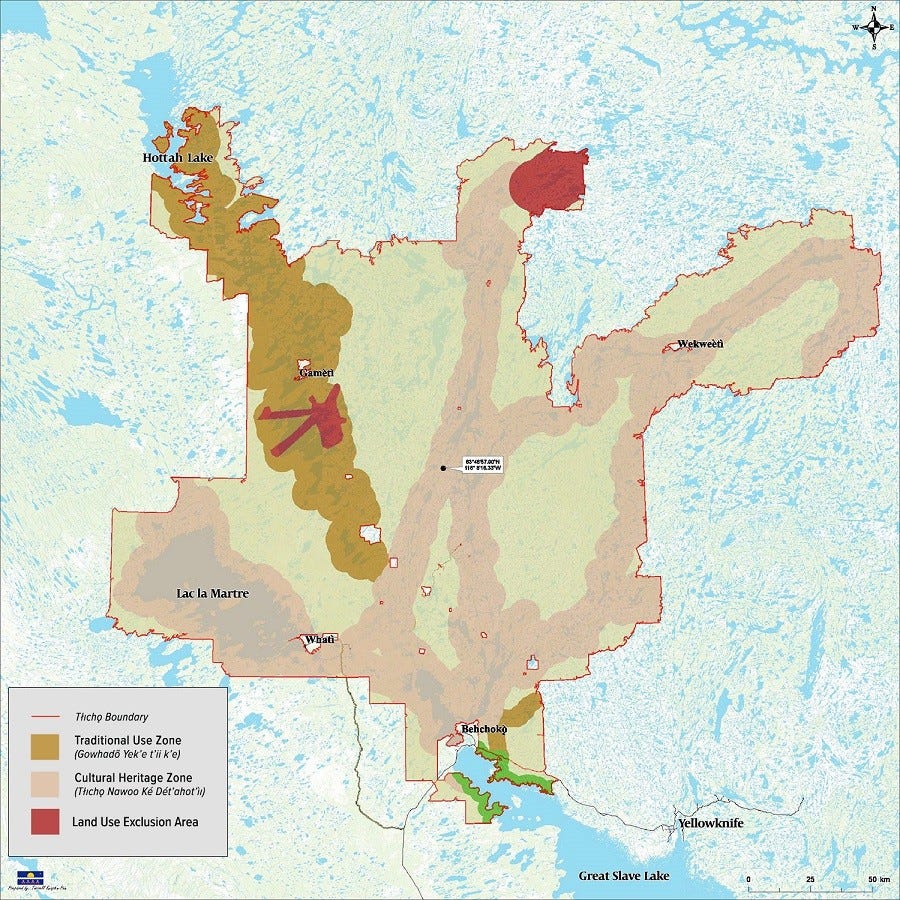

While there is no single recipe for a conservation area, the Tłı̨chǫ Lands Indigenous Conserved Area provides an example of what such an area can look like. This 22,000 km2 area contains five distinct management zones: an enhanced management zone, a cultural heritage zone, a traditional use zone, a habitat management zone, and land use exclusion areas.

While traditional activities such as hunting, berry picking, and the construction of small cabins are allowed across the whole conservation area, the allowed industrial activities vary by zone. On the most restrictive end of the spectrum, the exclusion areas and habitat management zones exclude industrial activities. However, in the least restrictive enhanced use zone, Tłı̨chǫ land managers will consider a range of industrial activities, such as mining, oil and gas development, and forestry.

Overall, the system of management zoning strives to protect values (such as caribou) that are integral to the traditional Tłı̨chǫ way of life, while still providing economic opportunities.

Humans as Part of the Natural Environment

One way to think about the difference between preservation and conservation is that whereas preservation seeks to protect nature by excluding human activity, conservation considers humans to be a part of their natural environment. For example, in Europe, much of the land base has been under human cultivation for hundreds or even thousands of years. Likewise, in the Northwest Territories, First Nations such as the Tłı̨chǫ have occupied the land since time immemorial. Therefore, human activities like farming (in Europe) and hunting (in the NWT) could be considered to be part of the local ecology.

I conclude this blog-essay with a personal anecdote. I once went to a presentation by an Austrian biodiversity researcher who described how the increasing industrialization of the European dairy industry was leading to a decrease in biodiversity on the Austrian landscape. With fewer herds of cattle grazing on the mountainsides, forests were encroaching on meadows. Human activity had traditionally contributed to the unique biodiversity of the region; as people moved to the cities, the natural balance was changing. This represented a new way of thinking to me as a North American.

The goal of “30 by 30” is to protect and enhance biodiversity. As people make up a part of this biodiversity, the goal of conservation should not be to exclude people from the land. Instead, it should be to balance the needs of people and nature.

“First Nations” is a Canadian term referring to Indigenous communities.