How the EU’s Definition of Forest Degradation Is Sparking Controversy in Canada

Defining forest degradation in terms of whether or not a logged site is replanted satisfies neither industry not the conservation community.

Forests are integral to biodiversity, global carbon balance, and human well-being. Therefore, deforestation (the conversion of forested land to other uses) and forest degradation (the reduction of a forest’s ability to provide the same environmental and/or economic values that it once did) are important environmental issues.

Unfortunately, while the definition of deforestation is relatively straightforward, degradation is much more difficult to define. What values need to be conserved, and how are they to be measured? The answer depends as much on philosophy and perspective as it does on science.

EUDR Degradation Definitions

The European Union’s new Regulation on Deforestation-free Products (EUDR) is a case in point. The regulation strives to ensure that the EU’s imports of forest products, soy, palm oil, cocoa, coffee, beef and rubber, and their derivatives, have not contributed to deforestation or forest degradation.

The EUDR looks at degradation in terms of biodiversity, stating in its preamble,

(15) Primary forests are unique and irreplaceable. Plantation forests and planted forests have a different biodiversity composition and provide different ecosystem services compared to primary and naturally regenerating forests.

In short, the key distinction is between what is considered natural (primary and naturally regenerating forests) and what isn’t (plantations and planted forests). However, in the Canadian1 context, the EU’s rather lengthy definitions still leave room for interpretation.

I have reproduced them here, because I believe they deserve a careful reading:

(7) ‘forest degradation’ means structural changes to forest cover, taking the form of the conversion of:

a) primary forests or naturally regenerating forests into plantation forests or into other wooded land; or

b) primary forests into planted forests;

(8) ‘primary forest’ means naturally regenerated forest of native tree species, where there are no clearly visible indications of human activities and the ecological processes are not significantly disturbed;

(9) ‘naturally regenerating forest’ means forest predominantly composed of trees established through natural regeneration; it includes any of the following:

a) forests for which it is not possible to distinguish whether planted or naturally regenerated;

b) forests with a mix of naturally regenerated native tree species and planted or seeded trees, and where the naturally regenerated trees are expected to constitute the major part of the growing stock at stand maturity;

c) coppice from trees originally established through natural regeneration;

d) naturally regenerated trees of introduced species;

(10) ‘planted forest’ means forest predominantly composed of trees established through planting and/or deliberate seeding, provided that the planted or seeded trees are expected to constitute more than 50 % of the growing stock at maturity; it includes coppice from trees that were originally planted or seeded;

(11) ‘plantation forest’ means a planted forest that is intensively managed and meets, at planting and stand maturity, all the following criteria: one or two species, even age class, and regular spacing; it includes short rotation plantations for wood, fibre and energy, and excludes forests planted for protection or ecosystem restoration, as well as forests established through planting or seeding, which at stand maturity resemble or will resemble naturally regenerating forests;

(12) ‘other wooded land’ means land not classified as ‘forest’ spanning more than 0,5 hectares, with trees higher than 5 metres and a canopy cover of 5 to 10 %, or trees able to reach those thresholds in situ, or with a combined cover of shrubs, bushes and trees above 10 %, excluding land that is predominantly under agricultural or urban land use;

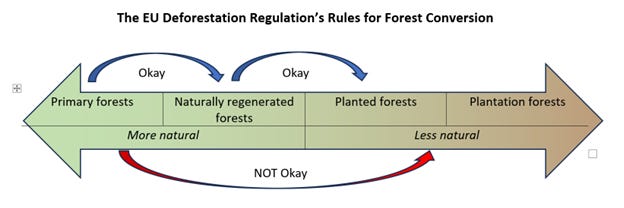

To summarize: under the EUDR, the “naturalness” of a forest could be described on a scale, with untouched primary forests on one end, and intensively managed forest plantations on the other (Figure 1). Moving just one step along the scale (i.e. a primary forest becoming a naturally regenerated forest) is not classified as degradation, but moving two or more steps (i.e. from a primary forest to a planted forest) does.

EUDR Definitions Examined With a Canadian Lens

Unlike European forests, many of which have been managed for generations, much of Canada’s forest harvesting occurs of forests that are being logged for the first time. Further, a common practice following logging is to replant, in order to ensure forests regenerate quickly and consistently.

A cursory glance at the EUDR definitions would suggest that Canadian forest practices would therefore be classified as “degradation,” as forests are being converted from “primary” to “planted.” However, a more careful reading suggests otherwise: the EU definitions state that “forests for which it is not possible to distinguish whether planted or naturally regenerated” also count as being naturally regenerated. As Canadian forests are planted with native species, and as the planted seedlings are usually joined by natural regeneration, this is almost always the case. Even when planted, under the EU definitions, most (if not all) Canadian second growth forests would count as “naturally regenerated forests” and therefore not be classed as degradation under the regulation.

There are good environmental reasons for planting trees. Tree planting ensures forests regenerate quickly, enabling them to begin sequestering carbon sooner. It can also help re-establish harder-to-regenerate species.

In a Canadian context, the main issue at stake is not so much the method of reforestation (planting vs. natural regeneration) as the species that is regenerated. In recent years, Canada’s reforestation practices have been criticized for emphasizing softwood species at the expense of hardwood species. While softwoods are more commercially viable, hardwoods contribute to biodiversity and act as natural wildfire breaks.

Competing Schools of Thought and Implications for Forestry in Canada

The conventional school of thought among Canadian foresters is that logging a previously-unharvested forest does not, in and of itself, constitute forest degradation. Logging is not the only event that can convert an old forest to a young one. For example, natural disturbances such as wildfire, insect outbreaks and windthrow are also relatively common.

A competing school of thought, popular among many environmental organizations (and widely publicized), is that much of the logging that occurs today actually does count as degradation. If logging occurs more frequently or across a larger area than would occur under a natural disturbance, the amount of old growth forest will decline over time. This decrease can threaten the survival of species that depend on large areas of old growth, such as mountain caribou.

Several environmental organizations have been lobbying governments to adopt this broader definition of forest degradation. To data, the Canadian government has been relatively tight lipped about the matter. However, the British Columbia government does appear to be moving in that direction.

The policy document Draft B.C. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Framework does not actually include the term “forest degradation”; however, in calling for the widespread adoption of “ecosystem-based management” it closely adheres to the philosophy that industrial disturbances (like logging) should mimic the pattern of natural disturbances. While a shift to ecosystem-based management has been broadly applauded by environmental organizations, it could drastically reduce the amount of timber available for harvest in BC.

Curious to learn more? I recommend Sustainable Forests readers, especially if based in BC, take a look at the Framework document and, if moved to do so, submit comments to biodiversity.ecosystemhealth@gov.bc.ca . The deadline has been extended to January 31, 2024.

Although this article focusses on Canada, the issue of old growth logging (or logging in “primary forests”) is also relevant to the US, where the Biden government has proposed to ban old growth logging in National Forests, and Australia, where the states of Victoria and Western Australia have recently banned logging in native forests.

Lost me a bit when you started talking about "UN definitions" and "UNDR". Was this in error and the intention to refer to "EU definitions" and "EUDR"? Otherwise makes good points. A problem with EU regulations in the forest sector is that they are drafted by technocrats with no understanding of forest dynamics or ecology and that do not consult adequately with forestry experts either at home or abroad. Instead they rely on narrow interpretations borne of European experience and strongly influenced by the views of European environmental groups and domestic politics. The result is a poorly drafted law which even a majority of EU Agriculture Ministers agree is "impossible" to implement.