Land Ownership, Politics, and Forest Policy

What can be done to better utilize forestry's untapped economic and carbon sequestration potential?

Many factors influence forest policy in any given jurisdiction.

A recent release by the BC Council of Forest Industries (COFI) provided food for thought. It compared forest management practices in three jurisdictions: Finland, New Zealand, and BC. Each is a major softwood producer. Also, each has a similar population (roughly 5 ½ million people), a democratic government, and a temperate climate.

However, the COFI report also highlights a major difference between the three jurisdictions: while BC has much more forested land area than either Finland or New Zealand, it harvests slightly less than half of what Finland does and only slightly more than New Zealand does. (Please click on the images to see a larger view).

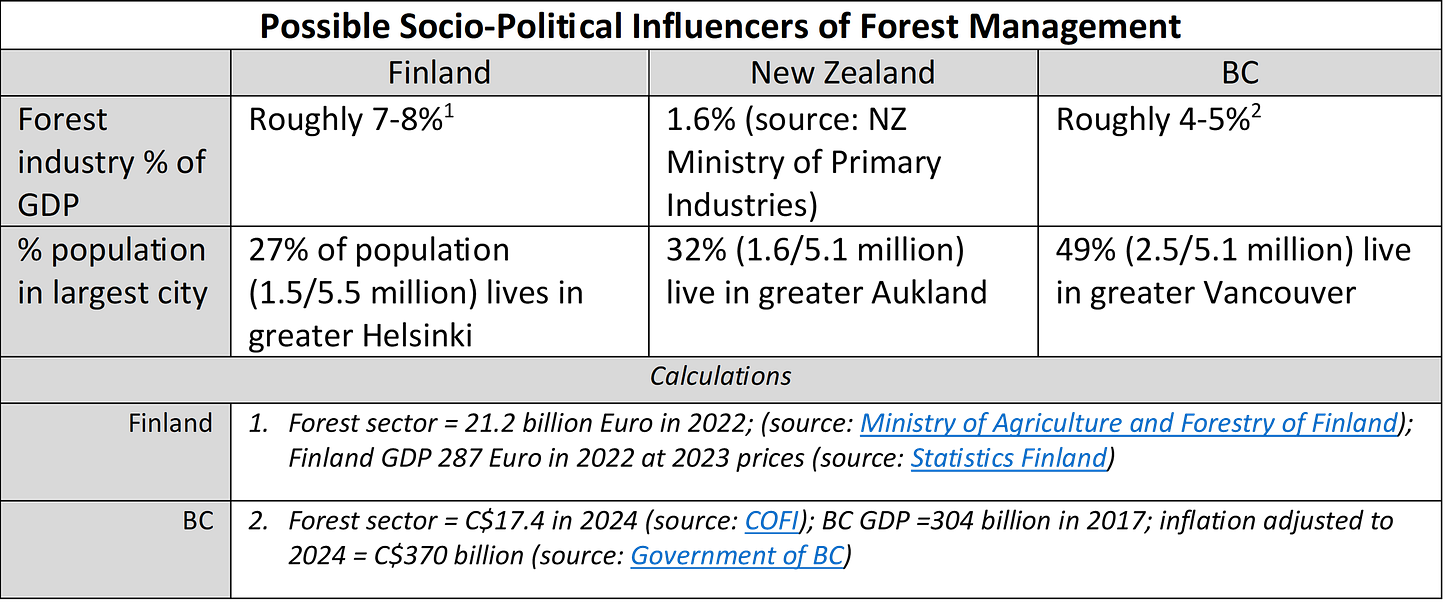

What is the main reason for this difference? The COFI report does not explicitly say. However, it does provide a statistical comparison:

The first difference on the list is ownership: while Finland’s and New Zealand’s forests are predominately privately owned, BC’s forests are 95% publicly owned.

Decision-Making Currencies

COFI’s report is careful not to point fingers.

As an independent blogger I can speak a bit more bluntly. BC’s apparent inability to reap the full economic and carbon sequestration potential of its forests may be linked at least in part to the public ownership of its forest land. In other words, the reason is rooted in government.

A basic assumption of economics is that individual land owners will make decisions in their own best interest. This includes both economic values (=money) as well as many other values linked to owners’ well-being.

On publicly-owned land (in democracies, at least), government officials make decisions with the well-being of the landowners in mind. However, while decisions on private land are made directly by the land owners, decisions on public land are made by government officials acting on behalf of the forest owners (the general public).

When guiding forest policy, politicians must consider how their decisions will affect their likelihood of getting re-elected. Thus, the key decision-making currency is not money but votes. If politicians perceive that their electorate believes their interests are best served by logging less, they will dictate this as policy – even if the overall result means less economic activity, government revenue, and carbon sequestration.

As shown above, the two jurisdictions with more privately-owned forests (Finland and New Zealand) harvest more wood per hectare of forest. But the public/private split may not be the only factor influencing forest policy. For example, Finland has a higher forest industry-to-GDP ratio and greater percentage of its population living outside of its biggest city. These factors likely also contribute to the nation’s industry-friendly policies.

Operating in a Politically-Charged Environment

So, what does this all mean for forestry companies operating on public land in jurisdictions where forestry isn’t seen as a priority?

The COFI report offers a subtle hint: the forest industry can stress how it is vital to dealing with issues that are a priority. For example, wildfire has become a hot-button topic in most of western and northern North America, as well as Australia, central Europe, and parts of South America. Climate-friendly housing is another.

This is a good springboard for a discussion. Within Sustainable Forests’ readership (yes, that’s you!), there are experts from around the world. So, here’s a question for you:

In your region, what programs, strategies, or tactics have worked well for raising the profile of forestry among industry officials and the general population? (And what has worked less well?)

Please, don’t be shy! Share your ideas in the comments box below.

Alice,

British Columbia's lands are owned by everyone and no one. Their chief steward is the provincial government. Once upon a time, there was a Forest Service and it released an an annual report to the public stating the condition of the land and the kinds of activities were being undertaken.

There is now not a forest service or an annual report. The government has reduced its forestry interface with the public by closing offices and reducing personnel, delegating its duties to professionals either working for industry or as their consultants. Public trust eroded faster than surface soil from a clearcut.

Meanwhile, when I was with the Canadian Forest Service, I co-authoured a research paper on improving the public trust in forestry in this province. It was approved for publication but the political powers of the day withheld its release while it was squelching the truth about the weaknesses in its cutting, pricing, tenure and oversight policies. Indeed, though professional reliance, the government apparently delegated its responsibilities to those who were reaping economic rewards while creating an environmental mess.

A few years ago, ex-forest minister Bob Williams published a paper called "Restoring Forestry in BC". It should be read by those of us that are concerned about government putting the interests of capital ahead of those of the people and the land.

Well…in more than forty years the single most effective tool for increasing public confidence in forestry were local based land use plans. Using consensus at a local level made forest and land management responsive to local values. Once industry was able to shift practices to better address local needs, confidence in the sector was improved. It was massively shortsighted to end land use planning and essentially cease local, meaningful public involvement, in the early 2000’s